Dr. Robert Snyder is Professor and Director of Clinical Research and Fellowship Director in wound care and research at Barry University School of Podiatric Medicine. He has created and implemented the first post residency Wound Management and Research Fellowship for podiatric medical schools. He is certified in foot and ankle surgery by the American Board of Podiatric Surgery and is also a board certified wound specialist. Dr. Snyder is past-president of the Association for the Advancement of Wound Care and past-president of the American Board of Wound Management, the certifying body for Wound Care Specialists. In addition to his doctorate, he holds an MSc in Wound Healing and Tissue Science from Cardiff University. His expertise at Cardiff, Wales, was further acknowledged as he was selected as an Internal Marker for MSc dissertations with an Honorary Title. To constantly expand his knowledge and stay current in all aspects of healthcare, he is completing an MBA in Health Management. Dr. Snyder is a key opinion leader and sought after speaker, lecturing extensively throughout the United States and abroad. He was chosen to develop and teach a wound care course for physicians internationally. Dr. Snyder has published several book chapters and over 150 papers in peer-reviewed and trade journals on wound care. He serves on the editorial advisory boards of Ostomy Wound Management, Wounds, and Podiatry Management and has recently been appointed as a periodic reviewer for the Lancet and NEJM. He has been a Principal Investigator on more than 50 randomized controlled trials for innovative wound healing modalities and products.

Joey Ead is currently a second year medical student at Barry University School of Podiatric Medicine. Prior to attending medical school, Mr. Ead received his Masters Degree in biomedical science with a concentration in wound healing and tissue regeneration. Mr. Ead has been involved in various research studies and has worked closely with wound care specialist Dr. Robert Snyder DPM, MSc, CWS.

Dr. Cherison Cuffy is a graduate of the University of Miami with a Bachelors of Science in Biology. He then pursued his Doctorate at Temple University School of Podiatric Medicine. Dr. Cuffy completed a three-year podiatric medicine and surgery residency at Northwest Medical Center in Margate Florida. After working several years in private group practice with a subspecialty in wound care, Dr. Cuffy joined the faculty at Barry University School of Podiatry as an assistant professor. He now participates in the clinical education of the podiatry students along with a focus on clinical research at the Paul and Margaret Brand Research Center.

Snyder, Ead and Cuffy_Current Dialogues in Wound Management_2018_Volume 4_Issue 3

“A driving force behind health care practitioners’ transition from being soloists to members of an orchestra is the complexity of modern health care.” – Pamela Mitchell, et al. October 2012

INTRODUCTION

Chronic wounds pose a major challenge in terms of their complexity and prevalence. In the United States, non-healing ulcers impact approximately 5.7 million individuals.1 Chronic wounds fail to proceed through an orderly and timely process to produce anatomic and functional integrity or have proceeded through the repair process without establishing a sustained anatomic and functional result.2The etiologies of non-healing ulcers are often complicated by multiple underlying comorbidities which make wound healing challenging. These include diabetes and vascular disease among others. Considering the systemic nature of these pathologies skilled clinicians and medical personnel are required, and a holistic approach remains paramount.

Many consider chronic wounds to be a “silent epidemic” that has often resulted in poor implementation and management strategies. Appropriate wound management treatment pathways should be patient centered, multidisciplinary, and holistically based. Many algorithms can be challenging and complex, which often leads to ineffective treatment pathways. Additionally, at many healthcare establishments, there may be no obvious wound care specialist; various clinicians in different fields devote several hours per week at wound care centers. Interestingly, they are viewed by the local medical community as general and podiatric surgeons, internists, surgeons, and vascular surgeons, not wound care specialists. It is therefore important that wound management clinicians have a distinct identity, and specialists be viewed as “woundologists.” Team-based health care models should be predicated on the following parameters: shared goals, mutual trust, clear tasks, effective communication, and established measurable processes and outcomes.

HOLISTIC MEDICINE AND CHRONIC WOUNDS

Holistic medicine is an integrative methodology that incorporates an array of various therapies to treat the patient as a “whole” (i.e., physically, mentally, and emotionally). A common mantra is to “treat the whole patient and not just the hole in the leg”. Chronic wounds can last several months to years. When these pathologies remain unhealed, it can cause an overall loss of function, reduced mobility, and decreased quality of life. Patients often succumb to infections that may necessitate amputations. The increase in an aging populationand chronic disease emphasizes the need for wound management to incorporate a more holistic approach. Optimal patient outcomes are largely predicated on a timely and accurate diagnosis. Patient-centered factors, including nutrition, obesity, uncontrolled infection, tobacco use, vascularity, pain, anemia, medications, and diabetes management, among others, can all obstruct healing.3 Once these parameters are assessed, a treatment plan can be implemented based on a patient/wound specific criteria. It should be noted that patient adherence to the treatment plan is strongly correlated to positive outcomes.3These algorithms should be agreed upon between the patient and the healthcare team. Holistic treatment pathways should include the patient’s overall function, homecare setting,

Figure 1. Synchronizing multidisciplinary networks for optimal patient care. Adapted from Sumpio et al. (Sumpio 2004)

Figure 1. Synchronizing multidisciplinary networks for optimal patient care. Adapted from Sumpio et al. (Sumpio 2004)

and a comprehensive risk assessment.3 Clear and direct communication will increase the likelihood that patients adhere to treatment plans.3 Some challenges with a multidisciplinary team include a discrepancy on values of autonomy and self-sufficiency. Additionally, the transition of many clinicians to evolve from “soloists” entities to members of a dynamic team may take time with a potential learning curve. Specialists generally function in silos: each clinician has a role and often “waits their turn” to perform a specific skill set. Direct communicationbetween specialists is often lacking.

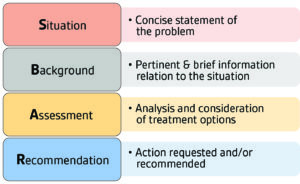

Figure 2. SBAR system can provide a framework for communication between respective wound management specialties.5

Figure 2. SBAR system can provide a framework for communication between respective wound management specialties.5

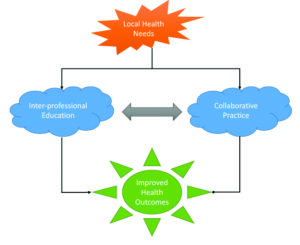

These challenges can be addressed by creating a team dedicated to wound management. This can be established by encouraging participation in multidisciplinary rounds. This fosters direct communication among different specialties to discuss, in real time, a patient plan of care and treatment decisions. Unfortunately, multidisciplinary care is often viewed as several disciplines working in parallel, with independent goals. This must change. One way of addressing this issue is to consider a transdisciplinary approach. This methodology connotes an organizational strategy that crosses many disciplinary boundaries, thus allowing team members to function more effectively and can provide patients with comprehensive treatment protocols (Figure 1).4 The Denver Health and Hospital Authority developed a situational briefing system called “SBAR” which is an acronym for Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation.5 This system aids in communication on a patient’s condition that requires immediate attention (Figure 2).5 It streamlines all pertinent patient information to every team member and for information to be transferred accurately. By encouraging collaboration, multidisciplinary teams are better able to work synergistically to promote an organizational culture of patient-centered care. Another potential solution is to create a weekly or monthly forum for interdisciplinary education that could include a variety of health care disciplines that collaborate through joint planning, decision-making, and goal-setting (Figure 3).

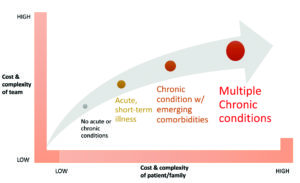

The importance of incorporating a multidisciplinary culture cannot be underestimated. No single person or specialty can provide all the services needed in patients with chronic wounds. Chronic wounds increase the cost and complexity of treatment pathways for clinicians, patients, and their families (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice.6

Figure 3: Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice.6

In Denmark, a multidisciplinary team integrated vascular intervention and wound management which resulted in a 75% reduction in lower extremity amputations.8 Increased healing rates may translate to more efficient use of resources. Standardized treatment provided by multidisciplinary wound care teams could lower costs and improve chronic wound healing in nursing homes.

Figure 4. Scaling team-based care with the increase of chronic conditions.7

Figure 4. Scaling team-based care with the increase of chronic conditions.7

The intensely hierarchical configuration of many health care institutions is counterproductive to a well-functioning and effective team where all members’ views and concerns are considered. A paradigm shift should move away from the “discipline” hierarchy approach to a patient-centered one in which the competencies for patient care are designed and crafted for individuals depending on their level of responsibility. To optimize patient care and outcomes, the medical hierarchy needs to be balanced in favor of a system that promotes dialogue and open communication. Implementing a feedback protocol is vital to promote a cohesive and collaborative medical team. Additionally, team “debriefing” sessions can assess and improve after-action procedures or policies. By including all members of the team, a focus can be placed on continually improving overall patient outcomes and encouraging multidisciplinary collaboration to reduce team conflict.10Developing procedural checklists can also bend the hierarchy curve and establish a continuum of care. Trust among team members must be at the forefront; clinicians need to leave their

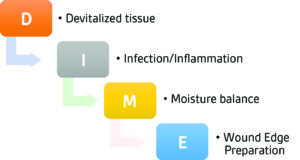

Figure 5. DIME (devitalized tissue, infection/inflammation, moisture balance, and wound edge and depth).11

Figure 5. DIME (devitalized tissue, infection/inflammation, moisture balance, and wound edge and depth).11

A holistic wound management cycle encompasses a consistent method of treating all chronic wounds, from arriving to a diagnosis to follow-up appointments.3 It is based on the identification of wound characteristics (or other pertinent symtomatology) to guide diagnostic pathways, understanding the principles of wound assessment, adequate patient and wound bed preparation, appropriate treatment, and proactive follow-up visits to help prevent recurrence.3 The steps in a holistic approach are not linear and should be repeated if the wound stagnates and displays no sign of healing.

Timely and accurate wound diagnosis is the first key step in formulating the proper treatment pathway of a chronic wound. Yet, making a correct diagnosis can be difficult due to potential involvement of numerous patient comorbidities and etiologies. Therefore, the center of every holistic “team” is the patient. This necessitates the need for a global framework when treating a patient’s local and systemic factors. Local factors refer to causes that directly affect the characteristics of the wound site itself. Systemic factors are related to the general overall health or disease state of the individual, which affects healing ability.3 A systematic approach to treating chronic wounds is imperative for optimal chronic wound outcomes. Clinical practice guidelines are frequently convoluted, complex, and at times difficult to follow. The wound bed preparation “DIME” model (devitalized tissue, infection/inflammation, moisture balance, wound edge, and depth) represents a powerful patient centered algorithm (Figure 5).11 It promotes accelerated endogenous healing and removes factors that hinder wound repair.11-13The first step of the wound bed preparation (WBP) model is to assess the patient and treat any comorbidities prior to wound treatment to eliminate potential wound healing barriers. A sequential approach and utilization of advanced wound therapies in tandem could lead to treatment pathway synergism.12,13In patients with diabetes, modifying the treatment plan should be considered if there is < 50% change in wound size in 4 weeks or the wound has stalled or not changed in a 2-week period.

Patients can also experience severe physical and emotional distress due to social isolation.14 Providing integrative (holistic) wound management involves addressing physical, psychosocial, and spiritual components of the whole person.14The Seven Balance Point Model includes holistic considerations that include sleep, nutrition, exercise, emotional, spiritual and social well-being.14 Nutrition is an important facet of the holistic care model. There are several factors that subject elderly patients to nutritional deficiencies which include medical comorbidities, physiological decline, psychosocial, and socioeconomic conditions.15However, one of the leading causes of malnutrition in the elderly population is the loss of appetite.15 This can make it difficult for these patient populations to meet their metabolic needs especially when these demands are increased by the presence of chronic ulcers.15It is critical for clinicians to screen for malnutrition in elderly populations by using the “Mini Nutritional Assessment” guideline.

The quality of life of patients with chronic wounds could be negatively affected by procedural or chronic pain, sleep disturbance, social, and emotional concerns.14 Integrative therapies could include biofeedback relaxation techniques (BRT), guided imagery, evidence-based dietary supplements, and medical grade honey among others.14 Rice et al conducted a randomized study of 32 patients that found when combined with standard care, patients who received BRT had increased healing rates.16 Results showed a higher healing rate in patients who used biofeedback-assisted relaxation techniques than in persons who did not (87.5% versus 43.8%, P <0.002) over 4 to 12 weeks; 21 patients were reported to be clinically positive healers, and 11 patients were reported as non-healers.16 Integrating adjunctive therapies can potentially help jumpstart the healing process.

CONCLUSION

Regardless of wound type or etiology, a holistic methodology should be implemented focusing on patient-centered concerns. Early and accurate diagnosis is the first critical step to ensure appropriate treatment pathways. However, arriving at the correct diagnosis can be a difficult task in the presence of numerous patient comorbidities and etiologies. The major tenants of a team-based health care methodology should include the following: mutual trust, shared goals, effective communication, and measurable processes and outcomes.7 Standardized multidisciplinary team-building protocols should be established that transcend and replace current traditional wound management practices. Wound bed preparation prior to treatment pathways is a well-established, evidence-based principle of wound care. It involves appropriate debridement, managing infection and persistent inflammation, moisture balance, and optimizing the wound edge. Patients with chronic wounds should undergo a nutritional assessment as part of their general wound management evaluation. Many integrative health and medical practices may have value in promoting wound healing, reducing pain, and promoting general health and peace for chronic wound patients. Proactive follow-up appointments are critical to prevent chronic wound recurrence and is an integral component in holistic wound and patient management cycle.

References

1.Frykberg RG, Banks J. Challenges in the treatment of chronic wounds. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2015;4(9):560–82. doi: 10.1089/wound.2015.0635.

2.Lazarus G.S., Cooper D.M., Knighton D.R., et al. Definitions and guidelines for assessment of wounds and evaluation of healing. Arch. Dermatol. 1994; 130:489–493. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1994.01690040093015.

3.Gupta, S, Andersen, C, Black, J. Management of chronic wounds: diagnosis, preparation, treatment, and follow-up. Wounds. 2017;29: S19-S3.

4.Sumpio BE, Aruny J, Blume PA. The multidisciplinary approach to limb salvage. Acta Chir Belg. 2004; 104:647–653.

5.Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: The critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:85–90.

6.Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/. Published December 21, 2015.

7.Mitchell P, Wynia M, Golden R, et al. Core principles & values of effective team-based health care. Washington, DC: Discussion Paper. Institute of Medicine; 2012.

8.Gottrupp, F, et al. 2001. Arch Surg 2001; 136: 765-772

9.Vu T, Harris A, Duncan G, Sussman G. Cost-effectiveness of multidisciplinary wound care in nursing homes: A pseudo-randomized pragmatic cluster trial. Fam Pract 2007; 24:372–379 doi:

10.1093/fampra/cmm02410.Zaccaro SJ, Rittman AL, Marks MA. Team leadership. Leadersh Q. 2002;12(4):451-483.

11.Snyder,R.J.; Fife,C.; Moore,Z. Components and Quality Measures of DIME (Devitalized Tissue, Infection/Inflammation, Moisture Balance, and Edge Preparation) in Wound Care. Advances in Skin and Wound Care. 2016;29(5):205-215.

12.Frykberg RG, Zgonis T, Armstrong DG, et al. American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. Diabetic foot disorders. A clinical practice guideline (2006 revision). J Foot Ankle Surg. 2006 Sep-Oct; 45(5 Suppl):S1-66.

13.Snyder RJ, Kirsner RS, Warriner RA 3rd, Lavery LA, Hanft JR, Sheehan P. Consensus recommendations on advancing the standard of care for treating neuropathic foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2010 Apr; 56(4 Suppl):S1-24.

14.Rosenbaum C (2012) An overview of integrative care options for patients with chronic wounds. Ostomy Wound Manage 58(5): 44–51.

15.Molnar, J. A., Underdown, M. J., & Clark, W. A. (2014). Nutrition and Chronic Wounds. Advances in Wound Care, 3(11), 663–681. http://doi.org/10.1089/wound.2014.0530

16.Rice B, Kalker AJ, Schindler JV, Dixon RM. Effect of biofeedback-assisted relaxation training on foot ulcer healing. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2001;91:132–141.