Ms. Susan Mendez Eastman is a certified wound care nurse and certified plastic surgery nurse at Nebraska Medicine where she has practiced for 25 years. She is an advocate for all patients and for the advancement of quality, evidence-based wound care that is available and affordable throughout the continuum of care.

Eastman_Current Dialogues in Wound Management_2018_Volume 4_Issue 4

Patients want to be partners in their care. My clinical experience suggests that most patients are attempting to preserve as much of their normal way of life as possible while managing a chronic condition, such as a pressure injury (PI). In my opinion, it is important to incorporate the goals of the patient into a treatment plan that can be coordinated by the entire healthcare team. Simply stated: the goals of the patient must merge with the knowledge of the clinicians resulting in a collaborative plan that keeps the patient at the center.

The care of a patient with a chronic PI should be driven by clearly stated goals. The overall goal of curative or palliative care of the injury must encompass the functional, physiologic, and emotional status of the patient and include the patient’s preferences along with the available resources. Patient preferences can differ significantly from the provider’s perception of their preferences. For example, a patient wants to see their loved one graduate from college, despite the fact that to attend the graduation, the patient would have to drive over 8 hours while sitting on a PI on their coccyx. The provider, knowing the detrimental effects of prolonged pressure over an already existing wound, could never endorse such reckless behavior. However, does denying the goal of the patient support the collaborative goal of healing? These decisions – to one degree or another – are faced daily in the care planning of a patient with a chronic PI.

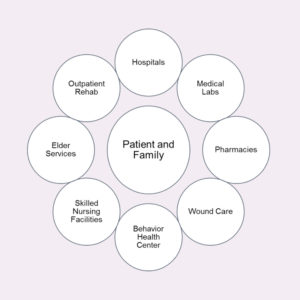

Patient-centered perspectives endorse empowerment and require us to re-think the typically paternalistic approach that healthcare has practiced for centuries (Figure 1). Patient empowerment is a process designed to facilitate self-directed behavioral change.1Empowerment is a process in which patients understand their role, are given the knowledge and skills by their healthcare provider to perform a task in an environment that recognizes community and cultural differences, and encourages patient participation.2 Emil Chiauzzi, research director at PatientsLikeMe, describes patient engagement from a much more symbiotic stance. Chiauzzi explains in an interview “I think the better way to look at it is that it is a skill that involves a variety of components, which has to do with problem-solving, communication, ability to seek out resources, an understanding of disease, and medical treatment associated with it.”

Practitioners often focus treatment on the wound rather than the patient. However, patients with chronic PIs most likely have multiple co-morbid conditions that interfere with wound healing.

Despite the fact that patients and their clinicians may both want treatments and therapies that are focused on healing the wound and preventing recurrence, patients come to the table with additional concerns that focus on their quality of life and the impact the injury may have on their family members, financial stability, functional abilities, and emotional well-being. These factors are often not considered by providers when developing a plan of care for a patient with a chronic wound.

Figure 1. Patient-centered approach to healthcare.2,3

Figure 1. Patient-centered approach to healthcare.2,3

In practice, patient-directed care begins with a skilled clinician eliciting patients’ health outcome goals and care preferences. Clinically feasible methods are available to help patients move from general values to SMART goals which are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound. Use of the SMART goals tool provides an approach that can integrate a holistic view of prognosis, clinical picture, and achievable outcomes.5 In response to the patient’s goals, the clinician presents care options from both the perspective of disease-specific outcomes, such as healing the PI, but does so within each individual patient’s desired outcome and care preferences.

Improving health and healthcare quality can occur only if all sectors – individuals, family members, payers, providers, employers, and communities – make it their mission to do so. Making healthcare more accessible, safe, and patient-centered is one of the three objectives of the National Quality Strategy, which was first published by the U.S. Department of Health Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in 2011. The benefit of these standards is its measures of patient experience, including interpersonal aspects of care, such as patients’ perceptions of how well their physicians discuss treatment options with them. Chronic wound care is not a recognized medical specialty, so the development of wound care quality measures has been left to other medical specialties that likely do not appreciate the impact of a chronic wound on the overall care of a complex patient.

The Institute of Medicine defines patient-centered care as “Providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs and values and ensuring that the patient values guide all clinical decisions.”6 The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 was also designed with the intent of raising the status of the patient’s wishes about his or her care. The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute defines its mission as helping people make informed healthcare decisions and improving healthcare delivery and outcomes through high-integrity evidence-based information. Research supported by this institute has demonstrated the importance of patients playing an active role in all their healthcare decisions. As a result of this research, patients, along with their caregivers, are encouraged to communicate with their healthcare providers and make their voices heard when assessments are being made about the value of various healthcare options. “One-size-fits-all” is not a realistic option in the world of healthcare decision making. Shared decision empowers patients and their healthcare providers to communicate better. It also encourages the active role of patients in the decisions surrounding their care and, thus, the likelihood that they will follow through with interventions and be satisfied with outcomes.

The patient with a chronic wound has additional obstacles related to establishing care for their condition. Society is generally not accepting of conditions that can’t be solved or are difficult to look at. So, patients often hide the fact that they are suffering from wounds. Wounds are an anatomical defect that may be malodorous, require frequent dressing changes, and be unappealing to the eye. Finding a practitioner who has experience managing chronic wounds is increasingly difficult in a healthcare environment that focuses on cures and pays for performance. There is no formal process for physicians to train, certify, and become credentialed in wound care.8 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education does not require chronic wound care education training and most family medicine residency programs do not provide specific wound care teaching for their residents.9So, patients are tasked with finding the rare provider who is knowledgeable regarding the care of a patient with a chronic wound and a provider who will engage, listen, and treat the patient holistically as an individual with specific needs, beliefs, and goals.

Another frequent barrier in achieving goals for chronic wound care is patient and family education. In my experience, providers become frustrated when patients are perceived to be non-compliant or non-adherent to a plan of care. When a plan of care is developed without the input or acceptance of the patient, it is likely to fail, and those failures are often blamed on the patient. When a patient-centered approach to a plan of care is utilized, and education is provided to substantiate the interventions or actions that drive the care, the patient is more likely to succeed in my opinion. In this model, patient concerns are discussed and considered as the plan is developed and updated. If a wound treatment or therapy is recommended by the provider, but the patient does not have adequate funds to purchase the needed products, a discussion can ensue, and alternatives considered. If pressure relief is required for extended periods of time and that time prevents the patient from working – and the patient is the primary source of income for the family – goals of healing may need to be re-defined. Durable medical equipment can be expensive and may not be covered by insurance. The inexperienced provider may be unaware that the off-loading or non-weight bearing requirements for recovery could necessitate a trade-off of food or medications as the activity orders impact the ability to work, which in turn limits income. Engaging the patient throughout the process of goal-setting, development of the plan of care, and the evaluation of progress provides ongoing opportunities for patients to impart their needs, beliefs, and expectations.

To further complicate the goals of a patient with a chronic PI is the all-too-often scenario when the patient has defined a goal and is unaccepting of the interventions required to achieve the goal. In other words, the goal is unrealistic, or the patient is non-compliant. If the informed patient has established a goal of healing from a chronic coccyx PI but will not accept the need to off-load the injury because of family obligations, living situation, co-morbid conditions, etc., it is the responsibility of his or her interdisciplinary healthcare team to go back to the stated goal. It has always been my experience that informed consent, education, and compassion should drive the provider and team to always keep the patient, not the wound, at the center of care.

In conclusion, patient-directed care begins with a skilled clinician eliciting patients’ health outcome goals and care preferences. Clinically feasible methods are available to help patients move from general values to SMART goals which are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound. Use of the SMART goals tool provides an approach that can integrate a holistic view of prognosis, clinical picture, and achievable outcomes. In response to the patient’s goals, the clinician presents care options from both the perspective of disease-specific outcomes, such as healing the PI, but does so within each patient’s desired outcome and care preferences.

References

1.Anderson RM, Funnell MM. Patient empowerment: Myths and misconceptions. Patient Educ Councs. 2010;79(3):277-282. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.025.

2.World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care: First global patient safety challenge, clean care is safer care. http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/tools/9789241597906/en/. Published 2009. Accessed September 25, 2018.

3.Heath S. How can providers drive patient empowerment in healthcare? Patient Engagement HIT. https://patientengagementhit.com/news/how-can-providers-drive-patient-empowerment-in-healthcare. Accessed September 25, 2018.

4.Neloska L, Damevska K, Andjelka N, Pavleska Li, Petreska-Zovic B, Kostov M. The influence of comorbidity on the prevalence of pressure ulcers in geriatric patients. Glob Dermatol. 2016;3(3):319-322.

5.Zimney K. SMART patient-centered value-based goals. Evidence In Motion. https://www.evidenceinmotion.com/blog/2016/07/14/smart-patient-centered-value-based-goals/. Published July 14, 2016. Accessed September 25, 2018.

6.The Eight Principles of Patient-Centered Care. OneView. https://www.oneviewhealthcare.com/the-eight-principles-of-patient-centered-care. Published May 15, 2015. Accessed September 25, 2018.

7.Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A, Walker E, Watson P, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ. 2010;341:c5146. doi:10.1136/bmj.c5146.

8.Ennis W. Wound Care Specialization: The Current Status and Future Plans to Move Wound Care into the Medical Community. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2012;1(5):184-188.

9.Little SH, Menawat SS, Worzniak M, Fetters MD. Teaching wound care to family medicine residents on a wound care service. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2013;4:137-144. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S46785.