Dr. Graham graduated with a baccalaureate degree in Biomedical Sciences from Grand Valley State University in 2009. He then went on to attain his Doctorate of Podiatric Medicine in 2014 from Barry University.Dr. Graham is currently in his 3rd year of podiatric medicine and surgical residency with the added credential of reconstructive rearfoot/ankle surgical training (PMSR/RRA) at Jackson North Medical Center in Miami, Florida. He also serves as the president of the Podiatry Overseas Association, a non-profit medical mission organization.

Joey Ead is currently a second year medical student at Barry University School of Podiatric Medicine. Prior to attending medical school, Mr. Ead received his Masters Degree in biomedical science with a concentration in wound healing and tissue regeneration. Mr. Ead has been involved in various research studies and has worked closely with wound care specialist Dr. Robert Snyder DPM, MSc, CWS.

Graham and Ead_Current Dialogues in Wound Management_2016_Volume 2_Issue 3

NOTE: As with any case study, the results and outcomes should not be interpreted as a guarantee or warranty of similar results. Individual results may vary depending on the patient’s circumstances and condition.

BIOCHEMISTRY OF CHRONIC WOUNDS

Chronic wound pathologies are a result of a complicated series of biochemical reactions in which normal instances jumpstart a dynamic wound healing cascade. The natural trajectory of wound healing consists of four key phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation and maturation/remodeling.1 The pathogenesis of chronic wounds is characterized by an imbalance of protease/protease inhibitor levels and a prolonged inflammatory state. The dynamic biochemical features of chronic wounds require clinicians to understand how to gather the pertinent symptoms and clinical features while effectively integrating a multi-modal treatment plan.

WOUND BED PREPARATION

Falanga et al defined wound bed preparation (WBP) as the management of a wound in order to accelerate endogenous healing or to facilitate the effectiveness of other therapeutic measures.2 WBP is a multifaceted treatment process that includes:

•Management of moisture balance (exudate control)

•Wound edge preparation2

•Debridement2

•Treatment of infection

These techniques reinvigorate the wound healing cascade by eliminating deleterious biochemical factors.3 Proper wound management encourages the sequential use of therapeutic products and/or surgical interventions by rebalancing the wound biochemistry and fostering growth factor production.3 Bacterial species that permeate chronic wounds compete with other cells for oxygen and produce enzymes that destroy

vital growth factors.3 Critically colonized wounds have the ability to depict subtle clinical manifestations such as:

•Pain4,5,

•Foul odor4,5

•Wound bed discoloration4,5

•Friable granulation tissue

Certain bacterial specimens are able to produce excess matrix metalloproteases (MMPs), which consequently inhibit the wound healing cascade.6 Robson et el stipulated that systemic antibiotics are unable to reach adequate tissue levels.7 This finding therefore demonstrates systemic antibiotics could be of limited value in re-establishing” bacterial balance in these dermatologic pathologies.7 The pivotal research conducted by Robson illustrates the need for a paradigm shift that incorporates the use of topical antimicrobials-antiseptics in conjunction with systemic treatment.

Gardner et al provided valuable insight on the validity of using clinical signs and symptoms to identify localized chronic wound infections and comparing them to the gold standard of quantitative wound cultures.8This research group found that signs specific to secondary wound infections are expressed more frequently than “classic” signs and symptoms.8 This finding elucidates that signs specific to secondary wound infections (discolored-friable tissue, serous exudate, foul odor) may be a more valid clinical indicator of infected chronic wounds.

Snyder et al examined quantitative biopsy results from a clinical trial to determine the accuracy of examination in the diagnosis of diabetic foot infections.6 Sample size included forty-four patients with diabetic foot ulcers (DFU).6 They were recruited for a pilot, randomized controlled, multicenter trial comparing two topical products.6 The protocol required assembling patients who did not display any signs of infection.6 Patients had 4mm tissue biopsy taken from their ulcer. Subsequently, the biopsies were quantitatively assessed for the type and number of bacteria present.

DATA RESULTS

•54% (25/44) of subjects had no detectable levels of bacteria6

•9% (4/44) of subjects had bacterial levels less than 106 cfu/g.6

•34% of patients had bacterial levels higher than 105 cfu/g

• (15/44); patients with any level of beta hemolytic streptococcus were included in this group

The results signify that the occurrence of infection in diabetic foot ulcers is clearly underestimated by clinical examination.6Clinical evaluation based on touch, color and smell is cost effective but subjective.6 However, implementing this method alone provides no valuable information regarding the most appropriate chemotherapeutic modalities of treatment or specific bacterial species involved. Addressing infection concerns with systemic antibiotic therapy may lead to the development of drug resistance. Due to the inherent challenges of diagnosing infections, clinicians should start the treatment process with antimicrobial dressings.6This intervention will adequately prepare the wound bed despite what meets the eye.

SEQUENTIAL THERAPY

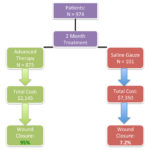

Sequential therapy is a treatment process that adapts to the stagnating conditions of non-healing wounds. By integrating multi-modal treatment processes, it helps remove barriers to healing, establish healthy granulation tissue, and re-establish proper vascularity to the wound bed with key sequence interventions. It is vital for clinicians to have a solid grasp of the biochemical variables that distinguish acute and chronic wounds. A literature review by Hanson concluded that if a wound can be re-dressed at longer intervals and if healing can occur more quickly, advanced product usage could be cost effective.9Snyder9 et al performed a retrospective study of patients receiving home care services. Researchers compared the results on lower extremity wound healing of using sequential therapy comprised of saline-soaked gauze versus advanced wound care products that included:

Nine hundred seventy four (974) persons fit the inclusion criteria; 873 had received C/ORC and C/ORC/silver and 101 had received the saline gauze treatment.9 Various wound etiologies were included in the study.9 They

Figure 1. (Flowchart that demonstrates cost-effectiveness and wound closure rates after a 2 month period: saline gauze v.advanced therapy); Adapted from Snyder RJ, Richter D, Hill M. A retrospective study of sequential therapy with advanced wound care products versus saline gauze dressings: comparing healing and cost. Ostomy Wound Management 2010;56(11A), 9-15.

Figure 1. (Flowchart that demonstrates cost-effectiveness and wound closure rates after a 2 month period: saline gauze v.advanced therapy); Adapted from Snyder RJ, Richter D, Hill M. A retrospective study of sequential therapy with advanced wound care products versus saline gauze dressings: comparing healing and cost. Ostomy Wound Management 2010;56(11A), 9-15.

Figure 2*. Maintain A. Theoretical Model: Cullen’s cycle — the vicious circle of delayed wound healing. With permission from Breda Cullen, Systagenix Wound Management IP Co B.V.9, B. Theoretical Model: Breaking out of the circle to encourage healing.

Figure 2*. Maintain A. Theoretical Model: Cullen’s cycle — the vicious circle of delayed wound healing. With permission from Breda Cullen, Systagenix Wound Management IP Co B.V.9, B. Theoretical Model: Breaking out of the circle to encourage healing.

found that 95% of the C/ORC and C/ORC/silver-treated wounds closed at a total cost of $2,145, compared to 7.2% of the saline gauze-treated group at a total cost of $7,350; 43% of saline-treated wounds healed by 6 months at a total cost of $22,050 (Figure 1).

The C/ORC/silver dressing has the ability to bind high levels of MMPs found in chronic wounds, consequently lowering protease and free radical activity.9 Vin F et al found that collagen based dressings accelerated healing in venous leg ulcers with 20% more wound healing.10 Additionally, they found that C/ORC/silver had a significant reduction in wound area in contrast to non-adherent dressing and compression alone.10 Nisi G et al conducted a study comparing C/ORC/silver versus moist wound healing techniques in the treatment of pressure ulcers.11 They found that more wounds achieved complete healing with C/ORC/silver (90% vs 70%), with shorter healing times, and proved to be more cost effective than control.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

This patient is a 64 year old male, who presented to the Emergency Department with a red, hot, swollen left foot. The patient stated his past medical history included: Type II diabetes, hypertension and peripheral vascular disease. During his emergency encounter, the patient stated he had a wound present on his left foot for approximately 3 weeks and the wound had not improved or worsened since its onset. During this encounter, patient was placed on Vancomycin/Zosyn.

At the time of the emergency room encounter:

Image 1: Day 1: Patient presents to the ER. Though not pictured, the infection was widespread to the dorsum of the foot. The infection was compromising the blood supply to the 1st digit, causing a dusky appearance.

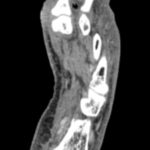

Image 1: Day 1: Patient presents to the ER. Though not pictured, the infection was widespread to the dorsum of the foot. The infection was compromising the blood supply to the 1st digit, causing a dusky appearance. Image 2: MRI left foot: Soft tissue emphysema can be visualized between the 1st and 2nd rays distally.

Image 2: MRI left foot: Soft tissue emphysema can be visualized between the 1st and 2nd rays distally.

•Blood glucose level was 467mg/dL

•White blood cell count 6.9 x10(3)/mcL

•Positive probe to bone testing

•X-rays suspicious for osteomyelitis

This patient was subsequently admitted to the hospital. An MRI was ordered to confirm radiographic suspicion of osteomyelitis, as well as to determine the extent of infection.The MRI findings were as follows: suspicious for osteomyelitis, distal 1st metatarsal and proximal phalanx of great toe, left foot; with soft tissue emphysema noted between the 1st and 2nd interdigital webbing.The patient was scheduled for an incision and drainage with debridement of all non-viable soft tissue and bone to the left foot, with possible partial forefoot amputation. Intraoperatively, it was determined to perform a partial 1st ray resection.

Image 3: Intraoperative image: New wound edges are defined, with healthy wound margins.

Image 3: Intraoperative image: New wound edges are defined, with healthy wound margins.

povidone iodine wet to dry dressings atop. Povidone iodine dressings were continued for 3 days after surgery. Subsequently cadexomer iodine paste was used for 1 week.During the outpatient follow-up phase of care, twice weekly debridement regimens were strictly followed for 2 weeks in conjunction with collagen/oxidized regenerated cellulose plus silver dressings, with an absorbent foam padding atop.

After the two-week period of C/ORC/silver therapy, the patient underwent negative pressure wound therapy. The NPWT was continued for approximately 3 weeks, allowing for an adequate amount of beefy red granulation tissue formation.

Image 4: The patient’s left foot on the final day of scheduled follow-up visits, 4 months after the initial emergency room encounter.)

Image 4: The patient’s left foot on the final day of scheduled follow-up visits, 4 months after the initial emergency room encounter.)

After the 3 weeks of NPWT, the patient was scheduled for an outpatient split thickness skin grafting procedure. The graft was harvested by the podiatry team from the patient’s left thigh. The graft was held in place with absorbable suture and was dressed with a non-adherent dressing with saline wet to dry dressings atop.

CONCLUSION

Sequential therapy is the cornerstone in tackling chronic wounds. The multi-modal process helps facilitate wound bed preparation and closure. Increased bacterial bioburdens are normally the main inhibitor of the wound healing cascade, which often necessitate topical antiseptics and debridement therapies to help transition the chronic into an acute physiological process. It is recommended that the aforementioned low-level silver dressings be applied in order not to affect the host cells’ biochemical environment (in contrast to high dose silver treatment). They assist clinicians in scenarios where infection is not traditionally observed, but an increased level of bioburden is suspected. Once the wound reaches bacterial stability the use of these advanced products should be discontinued. Based upon the wound response, patients could greatly benefit from several treatment modalities such as topical growth factors, ORC-collagen (silver), and living biologic skin equivalents.

References

1.Snyder RJ, Sigal B. (2005). The Physiology of Wound Healing. PODIATRY MANAGEMENT, 24(9), 187.

2.Falanga V (ed). New Concepts in Wound Bed Preparation. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag GmbH & Co;2003.

3.Snyder RJ. Rationale for sequential use of topical wound products – preparing and closing the wound. Podiatry Manage. 2007;June/July:3–6.

4.Gardner SE, Frantz RA, Doebbeling BN. The validity of the clinical signs and symptoms used to identify localized chronic wound infection. Wound Repair Regen. 2001;9(3):178-186.

5.Snyder RJ, Hanft JR. Diabetic foot ulcers—effects on quality of life, costs, and mortality and the role of standard wound care and advanced-care therapies in healing: a review. Ostomy/Wound Management 2009;55(11), 28.

6.Snyder, RJ Rationale for sequential use of topical wound products preparing and closing the wound. Podiatry Management 2007; 197-200

7.Robson, MC. Wound infection: a failure of wound healing caused by an imbalance of bacteria. Surgical Clinics of North America 1997;77(3):637-651.

8.Gardner SE, Frantz RA, Doebbeling BN. The validity of the clinical signs and symptoms used to identify localized chronic wound infection. Wound Repair Regen. 2001;9(3): 178-186.

9.Snyder RJ, Richter D, Hill M. A retrospective study of sequential therapy with advanced wound care products versus saline gauze dressings: comparing healing and cost. Ostomy Wound Management 2010;56(11A), 9-15.

10.Vin F, Teot L, Meaume S. The healing properties of Promogran in venous leg ulcers. J Wound Care 2002; 11: 335–41.

11.Nisi G, Brandi C, Grimaldi L, et al. Use of a protease-modulating matrix in the treatment of pressure sores. Chir Ital 2005;57(4):465–8.