Dr. A. J. Applewhite is the Medical Director at Baylor University Medical Center’s Comprehensive Wound Center in Dallas, TX, and Baylor Irving Wound Center in Irving, TX. He received his M.D. from the University of Texas Medical School in Houston and completed his Family Medicine Residency at UTMB. He devotes his full-time practice to wound care and hyperbaric medicine and has served as medical director for hyperbaric medicine and wound care centers since 2003. He is board certified in both Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine and Family Medicine. In addition to his board certifications, he is a Certified Wound Specialist Physician, Fellow of the American Professional Wound Care Association, Fellow of Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine (FUHM) and a Fellow of the American College of Hyperbaric Medicine. He serves as an Assistant Clinical Professor (Affiliated) for the Texas A & M Medical School, teaching medical students and residents about hyperbaric medicine and wound care. Dr. Applewhite is a paid consultant for Solventum.

Applewhite_Current-Dialogues-in-Wound-Management_2026_Article-1

Ulcerations secondary to edema related to chronic venous insufficiency remain a very common, yet somewhat unrecognized condition. Approximately 1% of individuals in the western world will experience a venous leg ulceration (VLU), and among those aged 80 years and older, 3% to 8% develop an ulceration due to venous insufficiency.1 Chronic venous insufficiency results from venous valvular incompetence and venous hypertension. Contributing factors can include inactivity, obesity, multiple pregnancies, trauma/injury, diabetes mellitus, vasculitis, neoplasm, and advanced age. Long-term management is challenging secondary to poor patient compliance and a high recidivism rate, with 12-month recurrence as high as 69%.2

Ulcerations due to venous insufficiency typically occur in the gaiter region of the lower leg and are generally shallow in appearance. They often contain granulation tissue, fibrinous tissue, and exudate, and can be quite painful. Additional findings may include hemosiderin staining, stasis dermatitis, and hyperpigmentation of the skin in the affected area of the lower leg.

Venous insufficiency can be a clinical diagnosis, though ultrasound may be required for confirmation. It is also essential to rule out concomitant peripheral arterial disease. If a VLU does not respond to standard treatment, other etiologies of lower extremity ulcerations should be considered. These include conditions such as vasculitis, pyoderma gangrenosum, skin cancer, and arterial ulcerations. A biopsy of the wound may be required for definitive diagnosis.

The standard of care for treating VLUs is compression therapy. Ulcerations secondary to venous insufficiency heal significantly faster once compression therapy is initiated. Compression therapy aids in reducing lower extremity edema, reduces pain associated with venous ulcers, and helps decrease inflammation. For patients with a normal ankle-brachial index (ABI), ≥0.8, a “regular” multilayer compression system that provides relatively high compression (30 to 40 mmHg) is indicated. For those with mildly reduced ABIs ranging from 0.6–0.8, a “light” multilayer compression system which provides 20 to 30 mmHg compression is appropriate.3

Topical treatment of the venous ulcerations is generally similar to the treatment of other wounds. Preparing the wound bed for healing includes removing/debriding any necrotic tissue, ensuring the bacterial bioburden is low, and managing the exudate. As most dressings we use will need to handle moderate to heavy drainage, applying a moisture barrier can help protect the peri-wound skin. Once compression therapy is initiated and edema and inflammation are managed, the amount of drainage typically decreases.

Several surgical options are available to treat chronic venous insufficiency, including laser sclerotherapy, subfascial endoscopic perforator surgery, ultrasound-assisted endoluminal radiofrequency ablation and “transilluminated powered phlebectomy. While these procedures can be effective, they do not immediately resolve edema, and the patient will still likely require long-term use of compression garments. In addition, lifestyle modifications such as diet, exercise, and weight loss are recommended, as they can significantly improve lower extremity edema.3

The following cases illustrate important considerations in treating lower extremity ulcerations which are secondary to venous insufficiency, with the primary aspect of care in each case being the initiation of a 3M™ Coban™ 2 Two-Layer Compression System.

Case 1:

A 45-year-old male with a medical history of atrial fibrillation, hyperthyroidism, and Grave’s Disease presented to the wound center with chronic wounds on the left leg, persisting for approximately one year. He had previously received care at another wound care center but sought a second opinion. Prior treatments included oral and systemic antibiotics, collagenase, silver dressings, and various topical therapies. The patient had declined the use of compression stockings or wraps. He reported no fever, chills, nausea, or vomiting.

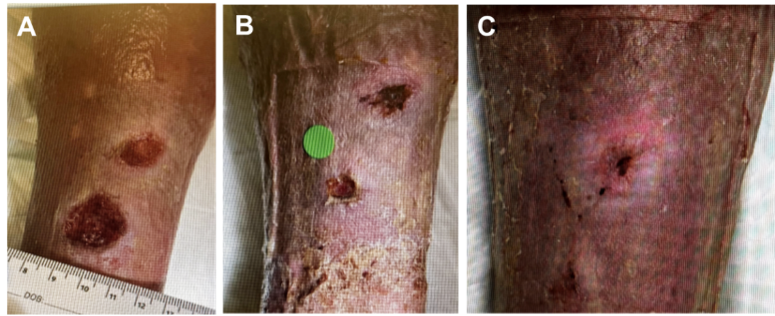

On physical examination, the patient had stable vital signs, was afebrile, and had a normal body mass index. There was 1+ edema in the right leg and 2+ edema in the left leg. The left leg demonstrated hemosiderin staining and a shiny appearance of the skin (Figure 1A). Two open ulcerations were present on the pretibial area of the left leg, both demonstrating nearly 100% granulation tissue with slight maceration noted around the edges. No devitalized tissue was observed. There was no peri-wound erythema, induration, warmth, deep probing, or malodor. No additional open wounds were noted. A venous Doppler study performed prior to the initial appointment was negative for deep vein thrombosis.

A 3M™ Promogram Prisma™ Collagen Matrix with ORC and Silver dressing was applied to the wound and covered with an absorbent secondary dressing. After an extensive discussion, the patient agreed to trial a compression wrap and was subsequently placed in a Coban 2 Compression System. The dressings were changed twice a week. Within 2 weeks, the wounds showed significant improvement, with reduced size and new epithelialization forming along the edges (Figure 1B). At 5 weeks, the more distal wound had completely epithelialized, allowing dressing changes to be reduced to once a week. After 8 weeks of compression wrap therapy, the wounds were completely epithelialized (Figure 1C).

This case illustrates that without addressing edema, chronic lower extremity wounds are extremely difficult to heal, despite the topical dressings used. Once compression wraps were applied and edema was addressed, these chronic ulcerations, which have been present for over a year, completely re-epithelialized within 8 weeks.

Case 2:

A 79-year-old male with a medical history of bilateral lower extremity deep vein thrombosis, anticoagulant medication use, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease,

gout, venous insufficiency, and chronic, recurrent lower extremity ulcerations presented to the emergency department with one week of swelling in his lower extremities and worsening wounds. He denied fever, chest pain, shortness of breath, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting. He reported significant drainage without purulence. The patient was able to bear weight, but ambulation was painful. He was not wearing compression garments. The patient was subsequently referred to the wound center.

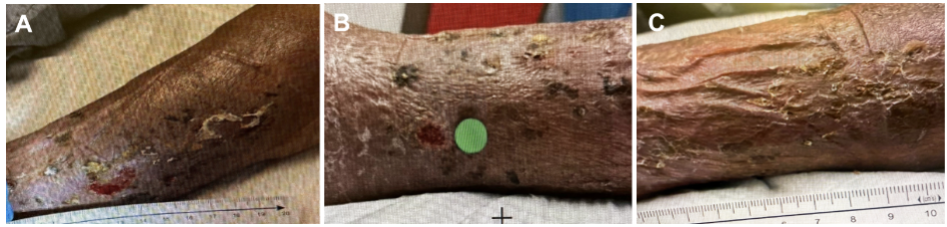

On physical examination, the patient had significant lower extremity edema with hemosiderin staining. A large, shallow open ulceration was present on his left lateral lower leg, flush with the surrounding skin and exhibiting healthy granulation tissue (Figure 2). There was a moderate to heavy amount of serous drainage, but no purulence or fluctuance. No peri-wound erythema, warmth, or malodor was noted. No additional open wounds were identified.

Promogram Prisma Matrix was applied to the left leg wound and covered with an absorbent secondary dressing. Coban 2 Compression System was then applied over the dressings. The dressings were changed twice weekly. Within 2 weeks, the wound had significantly decreased in size with new epithelialization formation (Figure 3A). Within 5 weeks of his initial emergency department visit, the wound was completely epithelialized and closed (Figures 3B-3C). The patient was advised that lifelong use of compression garments will likely be necessary. In addition, he was referred to vascular surgery for evaluation of his chronic deep vein thrombosis.

This case illustrates that even with treatment of the deep vein thrombosis with anticoagulation, managing edema is essential. Once compression wraps were applied, the large ulceration was fully re-epithelialized within 5 weeks.

Case 3:

A 78-year-old male with a medical history of atrial fibrillation and flutter, coronary artery disease, hypertension, hypothyroidism, myocardial infarction, and Parkinson’s disease presented to the wound center with a chronic ulcer on the right calf. The patient reported the wound had been present for approximately 2 months and had been left dry and exposed to air. He was taking sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, which was prescribed in the emergency department, but had not applied any topical treatment. The patient denied any prior history of leg wounds, as well as fever, chills, nausea, or vomiting.

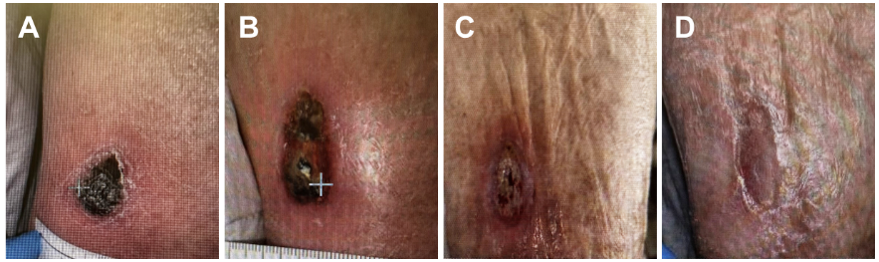

On physical examination, the patient had 2+ edema in both lower extremities, with a diminished pedal pulse in the right foot and a palpable pulse in the left foot. The ABI on the right leg was 0.5. A full-thickness ulceration with black, dry eschar was present on the right posterior calf (Figure 4A). No drainage, purulence, fluctuance, surrounding erythema, warmth, or malodor was noted. As the patient had evidence of significant peripheral vascular disease, compression therapy was initially contraindicated. An antibiotic cream was prescribed to treat the wound topically and help soften the eschar.

The patient was referred to vascular surgery for evaluation of peripheral arterial disease and subsequently underwent an angiogram and angioplasty. Two weeks after the initial presentation, vascular surgery cleared the patient for compression dressings (Figure 4B). The necrotic subcutaneous tissue was debrided from the wound base, revealing healthy granulation tissue. At that point, an antibacterial foam dressing impregnated with methylene blue and gentian violet was applied to the open wound, and Coban 2 Compression System was initiated with twice-weekly dressing changes. After 8 weeks of compression therapy, the right posterior calf wound was completely epithelialized and closed (Figures 4C-4D).

This case demonstrates that chronic venous insufficiency can occur in combination with peripheral arterial disease. In fact, approximately 30% of patients with venous insufficiency have concomitant peripheral arterial disease.4 It is essential to address peripheral arterial disease prior to initiating compression wrap therapy. Once compression wraps were applied, the wound completely re-epithelialized in a relatively short period.

References

-

Bergan JJ, Schmid-Schönbein GW, Smith PD, Nicolaides AN, Boisseau MR, Eklof B. Chronic venous disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(5):488-498. doi:10.1056/NEJMra055289

-

Simon DA, Dix FP, McCollum CN. Management of venous leg ulcers, BMJ. 2004;328(7452):1358-1362. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7452.1358

-

Fukaya E, Raghu K. Nonsurgical management of chronic venous insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(24):2350-2359. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp2310224

-

Ammermann F, Meinel FG, Beller E, Busse A, Streckenbach F, Teichert C, et, al. Concomitant chronic venous insufficiency in patients with peripheral artery disease: insights from MR angiography. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(7):3908–3914. doi:10.1007/s00330-020-06696-x