Dr. Tim Matatov completed his general surgery residency at Louisiana State University Health Shreveport and is board certified in general surgery. He is currently training in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Tulane University. He has published in the Journal of Vascular Surgery and the American Journal of Surgery and was invited to be a guest editor for the International Wound Journal.

Dr. Vemula completed his general surgery residency at Monmouth Medical Center in Long Branch, New Jersey and is currently training in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Tulane University. He has published in the Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and the Journal of Craniofacial Surgery.

Matatov and Vemula_Current Dialogues in Wound Management_2015_Volume 1_Issue 3

taINTRODUCTION

Nothing is worse than helping patients overcome an illness and then discovering they have acquired a new problem while hospitalized under your care. Although in a few situations pressure ulcers are unavoidable, they are usually a preventable problem. In fact, these wounds are thought to be so avoidable that, as of 2009, Medicare and Medicaid no longer reimburse facilities for Stage III and IV hospital-acquired pressure ulcers, regardless of the circumstances under which they occurred.1Pressure ulcers typically increase the length of a patient’s hospital stay by a factor of three and, on average, costs may be up to $100,000 per admission.2 This article reviews staging of pressure ulcers, risk factors, and treatment options. Failure to prevent pressure ulcers represents substantial liability, with 87% of lawsuits in favor of the patients.

PRESSURE ULCER STAGING

In the evaluation of pressure ulcers, the stage is the most objective and comprehensive description. Pressure ulcers are divided into four stages.

Stage I:Nonblanchable erythema present over a bony prominence. This may be difficult to detect in patients with dark skin tone.

Stage II: Partial-thickness loss of the dermis that creates a shallow ulcer with a red wound bed devoid of slough.

Stage III:Full-thickness skin loss with exposed subcutaneous fat, but no exposed bone, tendon, or muscle.

Stage IV:Full-thickness tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon, or muscle.

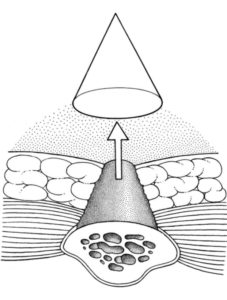

It is important to note that full-thickness tissue loss in which the depth of the ulcer cannot be accurately determined secondary to slough or eschar is deemed unstageable. The wound can only be staged once it has been debrided to expose the base. Also, skin is much more resistant to ischemia than muscle and, therefore, overlying skin may mask a much larger wound. Although the wound may appear small at the level of the skin, a large underlying wound base may be present. This phenomenon is referred to as the “tip of the iceberg” and must be accounted for in the assessment of these patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1. This picture is from Grabb and Smith’s Plastic Surgery 7th edition, Chapter 98, Page 990

Figure 1. This picture is from Grabb and Smith’s Plastic Surgery 7th edition, Chapter 98, Page 990

RISK FACTORS

Independent risk factors for pressure ulcers are advanced age, male sex, altered sensorium, moisture, immobility, malnutrition, friction, and shear injury. Most pressure ulcers occur secondary to sustained pressure or repeated ischemic events that happen without sufficient recovery time. Normal capillary filling pressures are 32 mm Hg at the arterial end and 12 mm Hg at the venous end. Therefore, any pressure greater than 32 mm Hg causes capillary collapse, which causes microthrombi, resulting in tissue ischemia and ultimately, a pressure ulcer.

Other forces that contribute to pressure ulcer formation are friction and shear. Friction can occur between the patient’s skin and any number of sources, such as bedding, stretchers, and slide boards. Shear force occurs when there is movement of the skin and superficial fascia over the fixed underlying deep fascia and bone. Excessive elevation of the head of the bed is one of the most common causes of unnecessary shear force.

Moisture increases the risk of skin breakdown and also increases friction. Advanced age, altered sensorium, and immobility all increase the amount of time pressure is placed on any particular area. Hypoproteinemia resulting from malnutrition impairs neovascularization, fibroblast proliferation, collagen synthesis, and wound remodeling.

PREVENTION AND MANAGEMENT

Preventive measures for pressure ulcers include pressure management, mindful patient transport, skin moisture management, control of spasticity, and maintenance of adequate nutritional support.

Two types of patient supports exist to provide pressure management: static support and dynamic support. Static support essentially consists of padding pressure points, using gel pads, sheepskin booties, wheelchair cushions, and mattress overlays. Dynamic support devices intermittently redistribute the pressure applied to the patient and consist of pulsating and air fluidized beds.

Nutritional support is a phrase highly touted in the medical community, and it is one of the least invasive ways to get the most beneficial results. Nutritional support must be emphasized as an integral part of the prevention and treatment plan. Data indicate that a serum albumin goal of greater than 2.0 g/dL is needed to promote adequate healing and prevent wound recurrence. Although values should be tailored to the individual, average protein intake should be 1.5 to 3.0 g/kg/day, with oral or intravenous supplementation as needed. Although supplementation with vitamin C has not been shown to expedite wound healing, deficiency is certainly deleterious. A well-balanced diet provides the vitamins and minerals shown to be important in wound healing, although multiple studies have failed to show clinical benefits to supplementation with zinc, arginine, and antioxidants. To achieve ideal nutritional support, consultation with a dietitian is strongly recommended.

Management of pressure ulcers outside the operating room includes sharp, enzymatic, or larval debridement, diagnosis and treatment of osteomyelitis, and wound coverage with appropriate dressings. Magnetic resonance imaging is the preferred imaging modality to evaluate for the presence of osteomyelitis, and a bone biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis. A patient diagnosed with osteomyelitis may require 6 to 8 weeks of antibiotic therapy before wound closure and up to 3 weeks of antibiotics postoperatively.8 It is important to note that biopsy cannot always distinguish between true osteomyelitis and surface osteitis. Surface osteitis, which can be caused by bone surface exposure at the wound base, can be easily treated by bone debridement and does not require intravenous antibiotics.

Selection of a dressing depends on the clinical status of the pressure ulcer. The presence of necrotic tissue, colonization or infection status, amount of exudate, and odor of the wound should be considered when selecting a dressing. For deeper wounds, negative pressure wound therapy has been shown to significantly reduce the wound volume and depth compared to standard wound care dressings; this option should be considered.9 Once the patient has been optimized, surgical management can be initiated. Principles of surgical management of pressure ulcers include excision of bursa, debridement of necrotic tissue and biofilm, and flap closure when appropriate. Primary closure has an unacceptably high recurrence rate, and skin grafts generally lack sufficient bulk and strength to cover the wound.

Although the technical aspects of flap reconstruction are beyond the scope of this discussion, I cannot emphasize enough that the flap cannot be made too big. Creating a larger flap facilitates any readvancement that may be necessary. Flap selection should ensure that future coverage options are not compromised.

CONCLUSION

Although pressure ulcers are identified as preventable complications, unfortunately they do occur. One conceivable approach to decreasing the incidence of pressure ulcers in the hospital setting may be to assemble a pressure ulcer team, similar to the peripherally inserted central catheter teams that exist now. The sole purpose of this group would be to minimize risks in patients identified by healthcare providers as having a high risk of pressure ulcers. This team would make rounds on these patients, manually turn them every 2 hours, and ensure they have appropriate bedding and padding. It is my hope that, with a more conscientious and proactive approach, the incidence of pressure ulcers, especially advanced-stage ulcers, can be significantly reduced

References

1.Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Program. Changes to the Hospital Services Medicare Program. Changes to the hospital inpatient prospective payment systems and fiscal year 2009 rates. Fed Regist. 2008;73:48472.

2.Description of NPUAP. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Adv Wound Care. 1995;8(4):Suppl 93–5.

3.Reddy M, Gill SS, Rochon PA. Preventing pressure ulcers: A systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(8):974–84.

4.Lindan O, Greenway RM, Piazza JM. Pressure distribution on the surface of the human body I. Evaluation in lying and sitting positions using a “bed of springs and nails.” Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1965;46:378-85.

5.Ladwig GP, Robson MC, Liu R, et al. Ratios of activated matrix metalloproteinase-9 to tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1 in wound fluids are inversely correlated with healing of pressure ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2002;10(1):26–37.

6.Janis JE, Kwon RK, Lalonde DH. A practical guide to wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(6):230e–244e.

7.Bauer J, Phillips LG. MOC-PSSM CME article: Pressure sores. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(1 Suppl):1–10.

8.ter Riet G, Kessels AG, Knipschild PG. Randomized clinical trial of ascorbic acid in the treatment of pressure ulcers. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48(12):1453–60.

9.The Accelerated Systematic Review of Vacuum-Assisted Closure for the Management of Wounds; Executive of the Council of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons; Dec 2003

10.Reddy M, Gill SS, Kalkar SR, et al. Treatment of pressure ulcers: A systematic review. JAMA. 2008;300(22):2647–62.

11.Rubayi S, Chandrasekhar BS. Trunk, abdomen, and pressure sore reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(3):201e-215e.

12.Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Kuzon WM Jr. An evidence-based approach to pressure sores. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(2):932-9.