Michael Robinowitz, M.D., earned his medical degree from Chicago Medical School in Chicago, Ill. He completed a residency and fellowship in obstetrics and gynecology at Emory University School of Medicine.Dr. Robinowitz joined Piedmont in 2009 as the medical director of the Wound Care Center in Fayetteville. Prior to joining Piedmont, he was in private practice at Nova OB/GYN in Atlanta and served as a Clinical Assistant Professor at Emory School of Medicine and Attending Faculty Physician at Grady Health System’s GYN/OB Clinic. He previously was in practice at Meridian Medical Group-Prucare of Atlanta where he served for some time as the President and Chairman of the Board.A fellow of the American Professional Wound Care Association and a diplomat of the American Board of Obstetricsand Gynecology, Dr. Robinowitz is board certified in obstetrics and gynecology and certified in wound care.

Robinowitz_Current Dialogues in Wound Management_2016_Volume 2_Issue 3

In part one of this series, the definition, scope and implementation of palliative wound care for patients was discussed in detail. This article will focus on specific treatments and remedies to ameliorate and modify some of the most common problems, ailments and concerns our patients face. The goal may not be to prolong life, delay progression of the disease itself or provide a cure. Remember, palliative care does not mean “no care;” its purpose is to prevent and relieve suffering and to increase the quality of life for people facing serious and complex illnesses.

The National Consensus Project Clinical Guidelines for quality palliative care defines palliative care as the following:

Palliative care expands traditional disease-model medical treatments to involve the goals of enhancing quality of life for patient and family, optimizing function, helping with decision making, and providing opportunities for personal growth. As such it can be delivered concurrently with life prolonging care or as the main focus of care.

It is estimated that one fifth of the U.S. population will be 65 years or older by 2030. Therefore, many more people will experience multiple comorbid illnesses as they age. There is limited information about wounds at the end of life. Reported prevalence rates vary between 30%3 and 47%4 and incidence rates vary from 8%5 to 17%6. There are numerous types of palliative wounds: malignant (5% of cancer patients) and pressure 13-47%.

In a large prospective sequential case study by Maida7, 67 of 472 cancer patients demonstrated malignant wounds at the time of referral to palliative care. Of these malignant wounds 67.7% were associated with at least one of the following 8 symptoms: pain, mass effect, esthetic distress, exudation, odor, pruritus, bleeding and crusting. Pain (31%) and mass effect (23.9%) were the most common complaints. Breast cancer patients had the highest prevalence of malignant wounds.

SYMPTOMS AND INTERVENTIONS

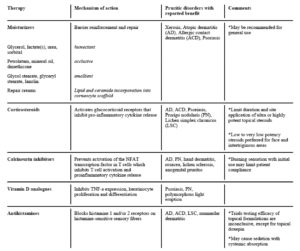

In this second article I want to focus on the common and frequent complaints/symptoms and the treatment options. Emmons8 et al have written in detail about common symptoms and interventions. (Table 1). I will go into more detail for some of the symptoms with special attention to less common, more esoteric and less traditional treatments.

PAIN

Pain can be broken down into several main types: cyclic (intermittent with repetition), noncyclic (single incident, e.g., cleansing and debridement) and chronic pain9 (Langema). Consider the following when thinking about the alleviation of pain: decreasing frequency of dressing changes, using non-adherent atraumatic dressings like silicone bandages or Vaseline gauze bandages, pretreatment with pain medication and changing saturated dressings10 (wet dressings are heavier and may cause more pain). Aside from changing the frequency of dressings, changing the type of dressing and changing the way a dressing is removed can be helpful. For example, when changing the dressing of skin tear type wounds where there is a secured epidermal flap, gently lift the dressing toward the flap opening, thereby preventing the skin from lifting up again. Placing an arrow on the dressing at the time of placement may help at the time of removal. Remember to consider the extent to which the pain medication may interfere with mobility, oxygenation, nausea, etc., and try to balance the pain relief against the undesired effects. For chronic pain, topical opioids have shown a clinical benefit in pain relief.11 Although off label (and not always practical), the use of intravenous morphine mixed with a hydrogel has been used successfully. Slow release ibuprofen foam dressings (not currently available in the US, but are in Canada and Europe) have also has been shown to be helpful.

Another way of decreasing dressing changes is to use light wrapping or other creative alternatives to hold dressings in place. Other strategies include naturopathy, essential oils, relaxation breathing and soothing music.

BLEEDING

Bleeding can occur from all types of wounds. It is most commonly seen in patients with breast cancer, head and neck cancer and primary skin cancers. Most bleeding is minimal and controllable. Using dressings that are non-adherent helps reduce the trauma and associated bleeding that may occur with dressing changes. Treatments are varied to include silver alginate dressings (which enhance the clotting cascade), topical vasoconstriction using epinephrine or oxymetazoline (Afrin®, Bayer), silver nitrate and electro cautery.

However, life-threatening bleeding CAN occur, sometimes with no risk factors or warnings and sometimes in patients at risk due to recent surgery.12 Risk factors include patients having radical neck dissection, prior radiotherapy, visible arterial pulsation and fungating tumors. Treatment includes identifying patients at risk, the use of multidisciplinary teams (if available) and indicated, and discussion with the patient and family to know what to possibly expect and what to do. If and when the bleeding commences, care should include general supportive and resuscitative measures and possibly specific surgical procedures such as ligation of large vessels. Occasionally, embolization13 done by interventional radiologists can be performed. Interestingly, mention is made of the use of dark towels and linens at these times in order to lessen the psychological trauma to the patient and family.

MALIGNANT AND FUNGATING WOUNDS

Fungating wounds occur in 5-19% of patients admitted to hospices. Fungating wounds will rarely heal and often will continue to grow. Care of these wounds is stressful and difficult for all caretakers, especially family. For the patient, they are a constant reminder of their infirmity and progression of their disease.

Complications of these malignant and fungating wounds include pain, odor, sepsis, bleeding, etc., and treatments are mostly the same as previously discussed. Disease control is the optimal goal, as is symptom control. Frequently one may need other modalities that ordinarily would not be used in patients when death is imminent. Using a multidisciplinary approach, modalities such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, interventional radiology, hormonal therapy and surgery should be considered.

Fujioka and Yakabe14 describe in detail two cases of surgery for fungating ulcers from breast cancer and melanoma that were treated with palliative resection and free skin grafting. The purpose of the surgery was to improve QOL (quality of life). In these cases, the QOL was improved by giving the patients the ability to stay at home which would not have otherwise been possible.

ITCHING

Pruritus (itching) is frequently associated with acute and chronic skin disease. Most clinicians are aware how debilitating itching can be, especially in patients that are dealing with one, some, or all of the previously described wound-related symptoms. A list of helpful medications can be found in Table 1.15(Elmariah and Lerner)

ODOR

Unpleasant odor is a problem of major proportion and personal distress to the ill patient. It is not uncommon for a patient to complain vociferously about an odor that is not evident to the persons taking care of the patient. Emmons et al describe common odor-related symptoms with intervention options. Other recommendations include: medihoney, topical oral chlorophyll, essential oils, burning candles, potpourri, vanilla and vinegar. If the odor is a result of bacterial overgrowth, then antimicrobial dressings may be helpful. In addition, activated charcoal is known to mask odor.

DRAINAGE

Some wounds can produce a large amount of exudate or drainage which can soak through clothing and lead to maceration, worsening of pressure ulcers, discomfort, and embarrassment. Several advanced wound dressings such as alginates, hydrofiber dressings, and foam dressings have absorbent capabilities of varying degrees.

CONCLUSION

The acceptance of palliative wound care is now part of our clinical thinking for seriously ill patients where complete healing is not possible. Remember, the aim of care is to improve the patient’s quality of life and to help them, as well as their family, retain their dignity in these difficult times.

References

1.Graves, Marilyn L., and Virginia Sun. “Providing quality wound care at the end of life.” Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing 15.2 (2013): 66-74.

2.Dahlin, Constance M. “National consensus project for quality palliative care.” Oxford Textbook of Palliative Nursing (2014): 11.

3.Chaplin, Jacqueline. “Pressure sore risk assessment in palliative care.” Journal of Tissue Viability 10.1 (2000): 27-31.

4.Bale S, Finlay I, Harding K.G. “Pressure Sore Prevalence in a Hospice.” J Wound Care. 1995; 4(10):465-466

5.Galvin, Jean. “An audit of pressure ulcer incidence in a palliative care setting.” International Journal of Palliative Nursing 8.5 (2002).

6.Langemo, Diane K. “When the goal is palliative care.” Advances in skin & wound care 19.3 (2006): 148-154.

7.Maida, Vincent, et al. “Symptoms associated with malignant wounds: a prospective case series.” Journal of pain and symptom management 37.2 (2009): 206-211.

8.Emmons, Kevin R., Barbara Dale, and Cathy Crouch. “Palliative Wound Care, Part 2: Application of Principles.” Home Healthcare Now 32.4 (2014): 210-222.

9.Krasner, D. “The chronic wound pain experience: a conceptual model.” Ostomy/wound management 41.3 (1995): 20-25.

10.Langemo D,Hanson D,Thompson p, Hunter S,Anderson Wound Pain J:Adv Skin Wound Care, 2009 June; (22): 255-8

11.Gallagher, Romayne. “Management of painful wounds in advanced disease.” Canadian Family Physician 56.9 (2010): 883-885.

12.Harris, Dylan G., and Simon IR Noble. “Management of terminal hemorrhage in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic literature review.” Journal of pain and symptom management 38.6 (2009): 913-927.

13.Broadley, K. E., et al. “The role of embolization in palliative care.”Palliative medicine 9.4 (1995): 331-335.

14. Fujioka, Masaki, and Aya Yakabe. “Palliative surgery for advanced fungating skin cancers.” Wounds 22.10 (2010): 247-250.

15.Elmariah, Sarina B., and Ethan A. Lerner. “Topical therapies for pruritus.” Seminars in cutaneous medicine and surgery. Vol. 30. No. 2. Frontline Medical Communications, 2011.